Cybersecurity’s Next Generation

CISOs are tapping new pipelines of talent. Recent hires reflect a greater diversity of skills and backgrounds.

Wintana Girma took an unusual path to a cybersecurity job. Previously an administrator in a doctor’s office in

Boston, she landed an executive assistant position with the chief information security officer at Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center. After impressing her boss with sharp analytical skills and an eagerness to learn, within six months he promoted her to security analyst.

“Everyone was very willing to let me listen in on their calls and whiteboarding sessions and answer my questions,” says Girma, now 33. “Just from that, I learned a ton.”

In her role, she performs third-party risk assessments to make sure Rush’s partners and vendors follow the medical center’s security protocols. She’s currently working toward a bachelor’s degree in health care administration, and aims to continue working in cybersecurity in health care.

IT leaders say that Girma is just the kind of person the industry needs to meet the soaring demand for cybersecurity jobs. Employment for information security analysts and engineers in the U.S. is projected to grow by 31% percent from 2019 to 2029, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Globally, the cybersecurity industry added more than 700,000 jobs last year, but the longstanding security-skills gap persists. The Aspen Institute’s Cybersecurity Group estimates that 500,000 info-security jobs in the U.S. alone will go unfilled this year.

Patching the talent pipeline

One problem is that there aren’t enough people coming out of four-year colleges to fill those roles. A report done by the state of California found that even if every student in an IT-focused college program were to go into cybersecurity, it wouldn’t be enough to fill all the available security jobs in the state.

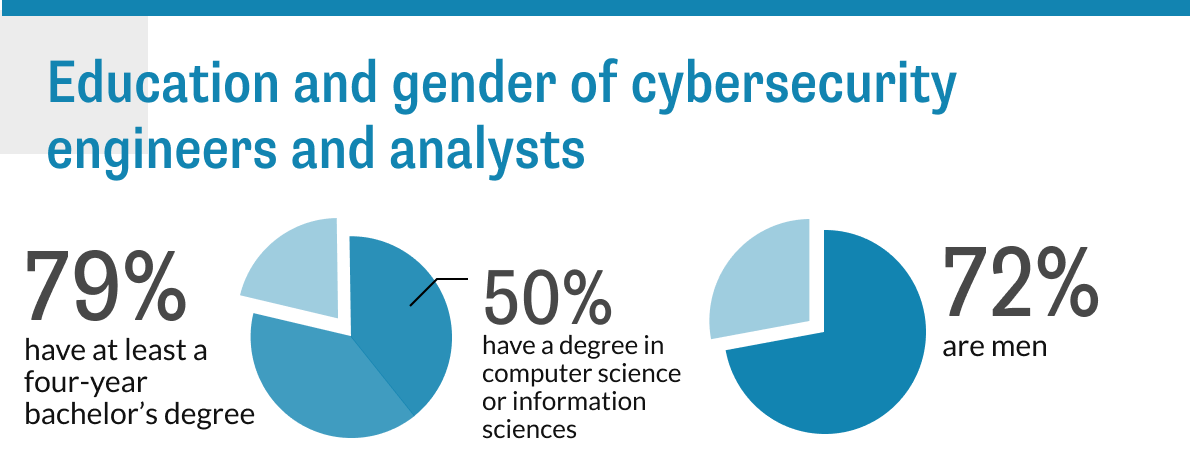

That means closing the massive skills gap will require looking beyond graduates of four-year college engineering programs to people like Girma, a Black woman with no previous technology experience. Currently, 79% of cybersecurity engineers and analysts have at least a four-year bachelor’s degree, half of them in computer science or information sciences, and 72% of them are men.

“If we’re looking at the four-year college system to supply enough people for cybersecurity, I don’t think we’re going to make the mark,” says Robert R. Ackerman Jr., managing director at AllegisCyber Capital. “There’s a lot of things that can be done with trained, skilled workforces that don’t have that four-year background.” Ackerman is among a chorus of cybersecurity and IT leaders calling for employers to embrace “new collar” workers, a term coined by former IBM chief executive Ginni Rometty to refer to people who may not have costly four-year degrees but who possess the foundational skills and natural aptitude for today’s in-demand, tech-based jobs.

Ackerman is among a chorus of cybersecurity and IT leaders calling for employers to embrace “new collar” workers, a term coined by former IBM chief executive Ginni Rometty to refer to people who may not have costly four-year degrees but who possess the foundational skills and natural aptitude for today’s in-demand, tech-based jobs.

At IBM, Rometty helped develop year-long apprenticeships that formalize the kind of hands-on experience and mentorship Girma was lucky to have found at her job at Rush. Of the nearly 100 people who have gone through the program in the past two years, 80% were offered full-time roles at IBM.

Mastercard sought outside help in training the next generation of cybersecurity analysts and engineers. In 2019, the company joined with a nonprofit to create the Cybersecurity Talent Initiative, a public-private partnership whose goal is to recruit and train “a world-class cybersecurity workforce.”

The program places participants—most of whom are women, minorities, or people who’ve decided to switch professions—into entry-level cybersecurity roles at a federal agency where they get experience and structured training. After two years, they can apply for jobs at one of the program’s corporate partners, which also include Microsoft and cloud software company Workday, and get $75,000 in student-loan assistance.

Lucinda Brooks: Late-stage career mover

Lucinda Brooks had already spent 25 years in network support and database engineering positions until she began considering a career shift. Intrigued by the increase in high-profile attacks in recent years, she decided to pursue opportunities in cybersecurity. Last year, she entered the Talent Initiative program, which placed her at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. She graduates next year.

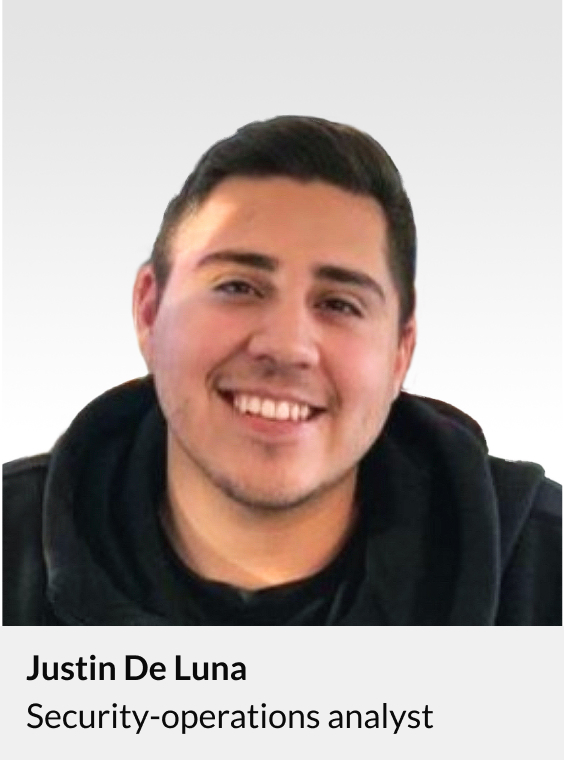

Justin De Luna: Online transfer

The growing number of online programs are also helping to fill the gap. Justin De Luna, an upstate New York native, spent his

post-high school years selling electronics in a variety of retail jobs before trying his hand selling mortgages and insurance. When he decided that his real passion was computers, he tried to parlay what he had learned on his own to get a job in IT. While working at the help desk for a credit union, he took an online course to get an associate’s degree, and then a bachelor’s degree in cybersecurity from Excelsior College. Last year, he landed a job as a security-operations analyst.

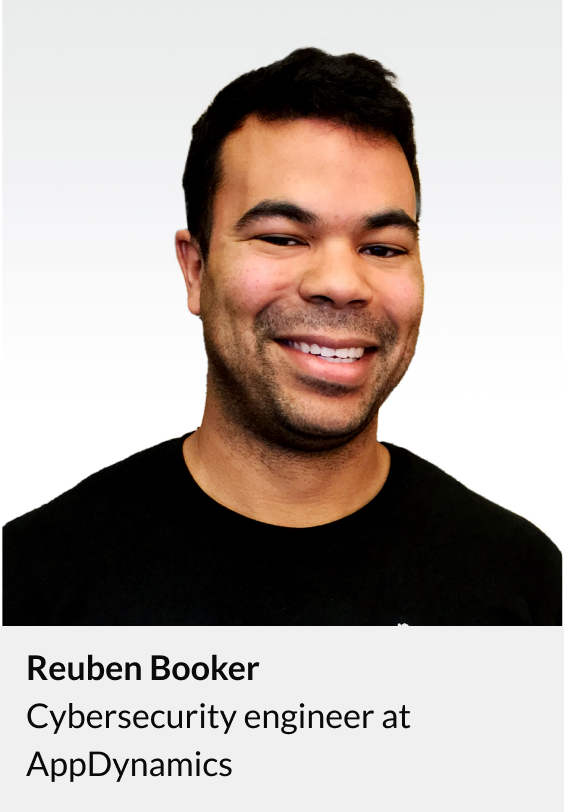

Reuben Booker: From DOD to IT

Military veterans are also an attractive pool of talent. Reuben Booker, in Portland, Ore., spent five years overseeing transportation logistics for the Army and another two managing a warehouse, but he craved a more mentally stimulating career. After enrolling in a 12-week cybersecurity-analytics boot camp at SecureSet Academy in Denver in 2017, he landed contractor gigs at Xcel and Nike. Last May, Booker, 35, was hired as a cybersecurity engineer at the IT operations analytics company AppDynamics.

These expanded cybersecurity-training programs, along with the growing number of two- and four-year colleges offering cybersecurity degrees, are a promising start, says Marian Merritt, director of the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education at the Department of Commerce.

Still, she says, it’s up to employers to recognize the value of both conventional and unconventional paths to their jobs. “They have to widen the aperture for who can apply and be considered for jobs,” she says, “and expand the mindsets about who a cybersecurity professional is.”