How State CIOs Are Digitizing in the Face of COVID-Era Budget Cuts

The pandemic is cratering state economies across the U.S. Here’s how the digital transformation battle is being fought today.

When California found itself staring at a backlog of 562,000 initial unemployment claims in late September 2020, it knew the culprit: a system that was asking state workers to track down, interview and verify the information submitted by more than 40% of applicants.

Governor Gavin Newsom convened a “strike team” to reform the state’s Employment Development Department’s claims system. Soon, the agency launched ID.me, an online tool claimants could use to verify their identities, bypassing the need for a follow-up call.

The result: Almost immediately, the tool reduced the initial claims backlog by 32%.

The California project exemplifies the challenges the pandemic has created for state CIOs. There’s never been more demand for IT services that help residents. At the same time, many state workers who deliver services are stuck at home and budgets are getting slashed.

Some state CIOs are responding with fast-to-deploy projects, built with emerging technologies, that automate functions states have traditionally delivered manually. To that end, they’re treating the pandemic as an opportunity for rapid digitization — even if that means kicking other tech-related challenges like security down the road.

“This crisis is forcing state CIOs to think about doing new things in new ways,” says Chris Estes, the former CIO for North Carolina and now the leader of Ernst & Young’s U.S. state, local and education practice. “In a weird way, the pandemic is going to force some tough decisions that will allow states to operate more efficiently. By reinventing how they deliver services to citizens, state CIOs will deliver them at a lower cost.”

[Read also: How the CARES act is driving tech investment in state and local governments]

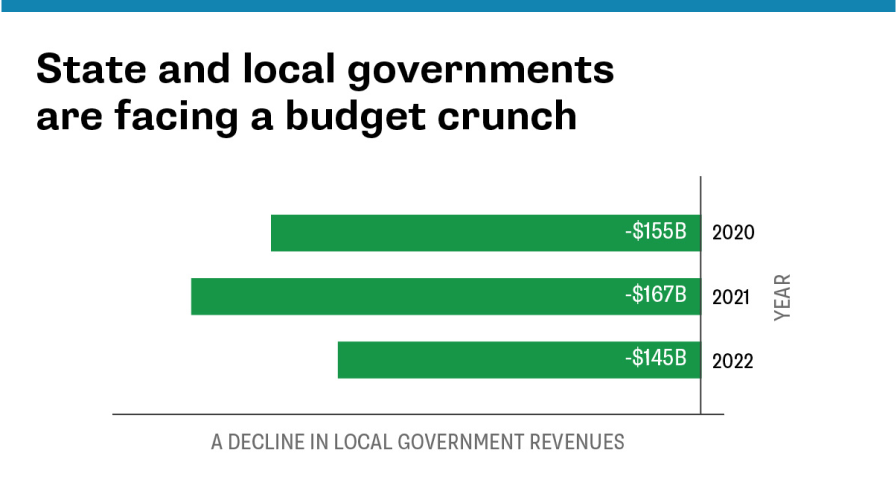

Those cost savings are much needed, as state and local government revenues are projected to decline $155 billion in 2020, $167 billion in 2021, and $145 billion the year after that, according to the Brookings Institution. The financial challenges are being felt coast to coast.

Increasingly the solution will be technology itself. “Most governors are looking at ways to reduce their operating expenses to make up for the budget shortfalls,” Estes says. “And often the way to do that, while still continuing to provide services to citizens, is to invest in technology.”

Quick projects, fast results

Colorado is one of the states expecting a budget shortfall. Yet Alex Pettit, its chief technology officer, plans to push for more spending on digitization.

“Digital transformation projects tend to be lightweight and pay for themselves in 12 months or less,” he says.

As evidence, he points to a project his office led, called Digital ID , that makes it possible for residents to apply for, and present, state driver’s licenses and IDs via a smartphone app. Launched in October 2019, the goal was to bring what’s a common consumer experience — using a phone for things like paying utility bills, reserving movie tickets and ordering takeout — to the slow lane of government services.

The effort has proved its worth during the pandemic. It has enabled residents to safely access state services without having to engage in face-to-face conversations with state agency workers. Since it launched, Digital ID usage has been growing 5% to 6% per month.

The project is a model for the ones Pettit wants to do moving forward — and he’s quick to identify the common thread. “In all of our digitization efforts, we’re trying to replace traditional in-person or paper transactions,” he says.

A newly urgent business case

One emerging technology that’s getting a fresh look from states is chatbots — AI-powered assistants that can help answer questions for residents about unemployment, public health and benefits, among other issues.

Prior to the pandemic, there wasn’t a clear rationale for states to adopt chatbots, says Amy Glasscock, a senior policy analyst at the National Association of State Chief Information Officers (NASCIO). Given the levels of pre-COVID calls to unemployment insurance offices and healthcare agencies, states reasoned they “had enough staff to handle the flow of things,” she says.

But the pandemic brought an unprecedented surge in inquiries, overwhelming call centers at many state agencies. “The pandemic was the defined business case,” says Glasscock, author of NASCIO’s 2020 study on states’ chatbot adoption during the COVID pandemic.

What states are now finding is that they can deploy the bots quickly and efficiently. For instance, this past spring, the Texas Workforce Commission received in 60 days the volume of claims it typically gets over 3.5 years. To handle that tsunami, the agency added workers and hours, but it also unveiled “Larry the Chat Bot.” It took just four days to get the tool up and running. By June it had answered 4.8 million questions from 1.2 million people.

Keeping secure amidst unprecedented demand

In their race to help residents and make it possible for employees to work from home, state CIOs may be creating — or at least leaving unaddressed — another challenge. These efforts, according to an October 2020 NASCIO cybersecurity report, have “highlighted shortcomings in the cybersecurity ecosystem.” But rather than invest to shore up these deficiencies, the report says states “made do with what they had.”

The study concluded that 46% of states have insufficient cybersecurity budgets, and that 54% fear being unable to keep up with cyberattacks.

This risk could be greater now that many state governments have transitioned their workforces, like so many other organizations, from on premise to remote. That means employees will be accessing sensitive information on citizens without the traditional protection of a network perimeter.

Depending on its size, a state could have millions of endpoints — desktop PCs, phones, internet-connected printers — in use every day. “Each one of those poorly protected soft targets now represents a pathway to the state’s servers,” says Egon Rinderer, global vice president of technology and federal CTO at Tanium. “If a hacker can get one of those endpoints, he can get into the enterprise and start going after the data.”

Hackers recently have targeted several states and their agencies. One incident occurred in Washington state: Bloomberg reported in late September 2020 that intruders had used phishing attacks to place the malware Trickbot on computers in at least 13 of the state’s departments and commissions, including parks and recreation, fish and wildlife, and corrections.

Finding the funds

Security typically doesn’t fit the low-cost, fast-to-deploy model gaining traction with state CIOs in the pandemic era. So where can they get the funds for these projects?

One possibility is the Federal CARES Act, which allocated $150 billion to state and local governments for pandemic-related projects. The list of states’ technology-oriented uses of CARES Act funds is fairly diverse, from $100 million for remote learning devices for schools in Alabama to $10 million for improving internet speeds for low-income Kansans and $10 million to connect Mississippi first responders to hospitals. Tellingly, cybersecurity has rarely been a focus for CARES-related projects.

As states forge ahead under anemic budgets, many policymakers will promote digitization efforts that make life easier for residents and cut costs. But they shouldn’t forget about security.

“One goal everyone should have is understanding the importance of funding for digitization projects,” says Colorado’s CTO Alex Pettit. “But it’s equally important to understand the funding for cybersecurity and to know your vulnerabilities.”