Zero Trust’s Time Has Come

The pandemic is driving adoption of this take-no-chances approach to cybersecurity.

When the pandemic hit, PPG Industries, a 137-year-old maker of industrial coatings and paints, was ready to keep operations going. A decade earlier, when the G8 Summit came to Pittsburgh, city officials, citing security concerns, asked the company to have the 12,000 employees in its downtown office work from home.

“We were really nervous about our ability to support all those people who couldn’t work from the office,” says Dan Connelly, the executive in charge of the company’s remote access efforts.

That got the company thinking: What would it do if another sudden event forced an even bigger shift to WFH? As a result of that exercise, the company purchased seven times more remote access capacity than it needed at the time. And it tightened up its security practices to limit network access to people who could prove their identity and the health of their device, each and every time they logged on.

When COVID-19 hit, “we were ahead of the game, and didn’t have to jump through a lot of hoops,” says Connelly.

Now, PPG is moving closer toward this take-no-chances approach to security. The model, known as zero trust, is quickly emerging as a pandemic best practice. Its goal is to safeguard computer networks from malicious intrusion by treating every device that tries to log on as a potential threat.

With millions of remote workers accessing organizational networks every day — and with IT teams overwhelmed by the amount of traffic and myriad unknown devices — zero trust is suddenly a pressing C-suite issue.

“In today’s WFH world, zero trust is essential,” says John Pescatore, the director of emerging security trends at the SANS Institute. “It’s like wearing a mask in public. Not doing so runs the risk that you might die or cause someone else to die. More than ever, bad security hygiene can be disastrous.”

Many business executives and IT teams have already gotten that message. Some 37% of executives at organizations with zero trust security initiatives are accelerating their efforts, according to a September 2020 Deloitte survey. Among the reasons: 60% of those polled by Enterprise Management Associates (EMA) also said they’d seen an increase in the number of security issues during the pandemic.

Today, the ability to work remotely is no longer a rare privilege granted to certain executives and field employees. Now, pretty much everyone needs remote access to the network to work. According to the EMA survey, the percentage of employees who primarily log in to work remotely has doubled since the pandemic began, to 62%. And two-thirds of the companies polled said they had allowed more employee-owned devices onto the corporate network.

This expanding universe of devices gives bad actors more potentially vulnerable targets. Since the pandemic began, 63% of cybersecurity experts polled by the Enterprise Strategy Group reported an increase in attempted cyberattacks. Historically, more than 90% of all attacks involve phishing, in which employees click on an artfully written email that lets the sender steal credentials or worse. But working from home alongside spouses, kids and pets, sometimes via unsecure Wi-Fi networks, compounds the problem. “All kinds of things can happen,” says Gus Hunt, former CTO of the Central Intelligence Agency, “including my kid downloading an insecure application to my PC.”

Creating a zero trust model

Even under the best circumstances, building a zero trust environment is difficult. It requires advance planning from a broad swath of people. These include top-level executives who understand what employees will tolerate as well software developers who know how to write code that automates those managerial insights into foolproof processes to make sure everyone follows the security rules — without slowing down work too much.

To make this happen, zero trust also requires companies to take another buzzword just as seriously: DevSecOps. Rather than operate as distinct teams with their own traditions and practices, those developers need to work continually with the IT staff who run the network and the applications that run on it, and the security experts who know how to spot and respond to new threats.

While achieving zero trust security is difficult, the basic concept of how it works is fairly simple.

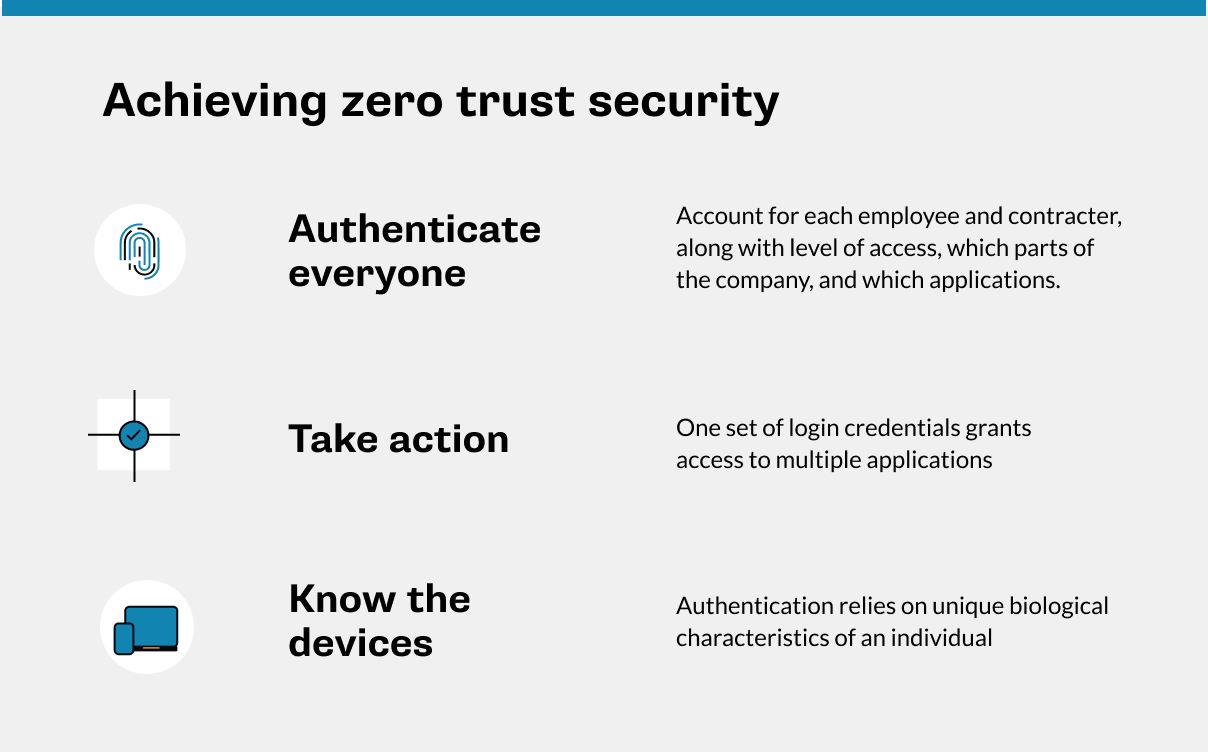

- Never trust, always verify: IT must work with all lines of business to make sure each worker and contractor is properly accounted for, including what level of access they should have to which parts of the company and which applications. Only then can their identity be authenticated, every time they log on. Without authentication, nobody gets access to a zero trust network.

- Know thy devices: Zero trust security means identifying not just who is trying to gain access but over what device. Under this model, only previously verified devices are granted access. But before that happens, the system needs to affirm several things: Is the device properly configured? Is it company-owned or employee-owned? If it’s the latter, does it have the right partitioning software to secure work-related activity while keeping personal data private? Are the operating system and applications updated? Do they have all the latest security patches? Is it running unsanctioned applications or has it been used to access unauthorized websites?

Surprisingly few companies take these precautions, particularly those rushing to accommodate WFH after the pandemic hit. More than half of employees now use their personal laptops and PCs for work, but only 39% have been given technology by their employers to make sure they are properly secured, according to a Work From Home study by IBM.

“You always need to know the status of every device, including what’s been downloaded onto it and who the user is,” says Hunt. “Only then can you create a system that can make good, automated decisions about who can do what.”

- Take action: A zero trust architecture doesn’t just spot potential threats. It can respond to them by, say, triggering an automatic software update, notifying a security staffer about a piece of malware or quarantining a system to cut off the device from sensitive data.

Start with good governance

Hunt says the most difficult task in implementing a zero trust model is setting the policies around who gets access, when and why. This first step, he adds, is the one that’s most often mismanaged. That’s because organizations don’t take enough time to understand how their workers use technology. For example, says Hunt, if a user logs on from an unusual location or with an unknown device, that doesn’t mean the user is a threat. Rules are just needed to accommodate that worker.

“If it’s really odd for Gus to be logging in from a Starbucks on a Sunday morning, maybe the system should let me in but only let me fill out my timecard and not give me access to the HR system or to any other sensitive data,” says Hunt by way of example.

[Read also: Building a zero trust future]

In other words, context is crucial. So if a device has a link to an unknown website but the user is verified as the company’s CEO, you may want to set rules that still allow her into the CRM system. Meanwhile, a subcontractor with little company history could go straight to quarantine.

Setting these detailed policies requires more collaboration than companies expect. Typically, to start down the zero trust path companies create a data governance board, but they too often fail to assign the people who know how workers work. That means in addition to IT and software development leaders, you need to include line-of-business leaders who know their teams.

“This is the hardest part,” says Hunt. “Policies and governance issues need to be thought through way ahead of time. You can’t just decide you’re going to do zero trust and slap it together.”

Making zero trust frictionless

Despite having worked on the problem for years, even Pittsburgh Plate Glass has a long way to go, says PPG’s Connelly. In some ways, his department has taken the easy way out by only allowing corporate-issue laptops, preloaded with security software, onto the corporate network. That means employees can’t use their own PCs, Macs or smartphones.

But in other ways, it hasn’t been careful enough. For example, once PPG employees do get on the network, they have free rein to use most applications and see most data. A perfected zero trust system would provide access only to what they are approved to use.

Going forward, Connelly says employees will expect to have many device options, and companies need to maintain finer control over how, when and where they are used.

“We don’t think people’s desire to work from home is ever going away,” says Connelly, whose company is gradually shifting from its own data centers to cloud-based infrastructure and services. “As we move to the cloud, zero trust will be a high priority for us,” he says.

Given the added complexity of keeping safe in a WFH world, companies will need to pay particular attention to balancing security and employee experience. Is IT disrupting how people work by putting up too many barriers? Just as a diner may not want to go to a restaurant that tested her for COVID-19 each time she walked through the door, workers don’t want to go through too many login hassles or wait too long for status checks before they can get any work done.

If the daily security hassles of just logging on become too onerous, companies risk giving employees a reason to think about jumping ship — or worse, make them look for shortcuts that reopen vulnerabilities. “When people get frustrated, they look for workarounds,” says Hunt.

Still, companies and workers can no longer place zero trust on permanent hold. “You can’t just hope breaches won’t happen to you. That’s no way to live,” says Pescatore, the analyst from SANS Institute. “Zero trust can prevent attacks that can screw up your whole company. It can no longer be considered optional.”